When we started building a durable workflows library, the most critical architectural decision we faced was what data store to use for workflow metadata. The core durable workflow operations are simple–checkpointing workflow state and recovering an interrupted workflow from its latest checkpoint. Almost any data store can handle these operations, but choosing the right one is critical to ensure workflows are scalable and performant.

In this blog post, we’ll dive deep into why we chose to build on Postgres. While there are good nontechnical reasons for the decision (Postgres is popular and open-source with a vibrant community and over 40 years of battle-testing), we’ll focus on the technical reasons–key Postgres features that make it easier to develop a robust and performant workflows library. In particular, we’ll look at:

- How Postgres concurrency control (particularly its support for locking clauses) enable scalable distributed queues.

- How the relational data model (plus careful use of secondary indexes) enables performant observability tooling over workflow metadata.

- How Postgres transactions enable exactly-once execution guarantees for steps performing database operations.

Building Scalable Queues

It’s often useful to enqueue durable workflows for later execution. However, using a database table as a queue is tricky because of the risk of contention. To see why that’s a problem, let’s look at how database-backed queues work.

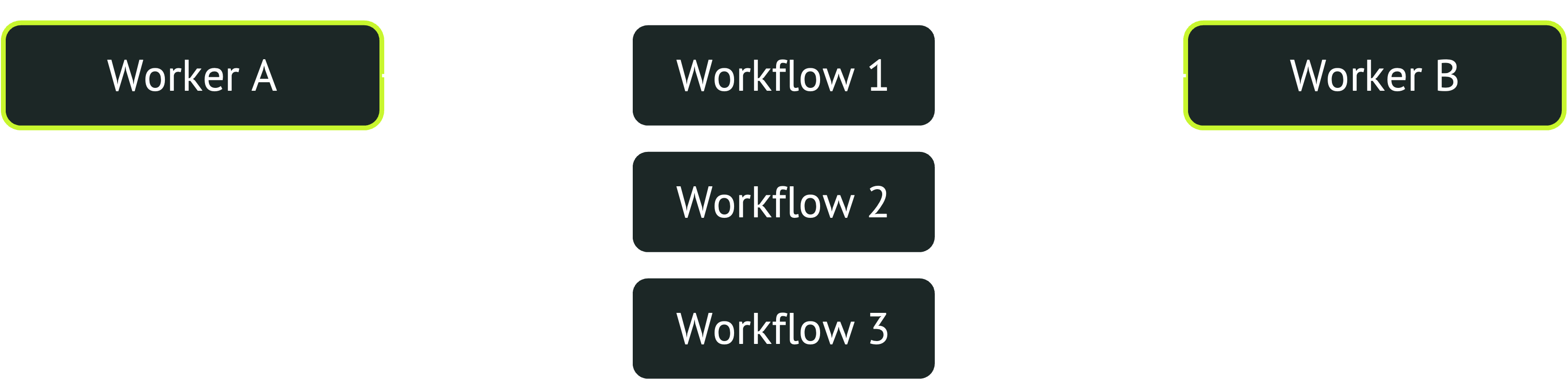

In a database-backed workflow queue, clients enqueue workflows by adding them to a queues table, and workers dequeue and process the oldest enqueued workflows (assuming a FIFO queue). Naively, each worker runs a query like this to find the N oldest enqueued workflows, then dequeues them:

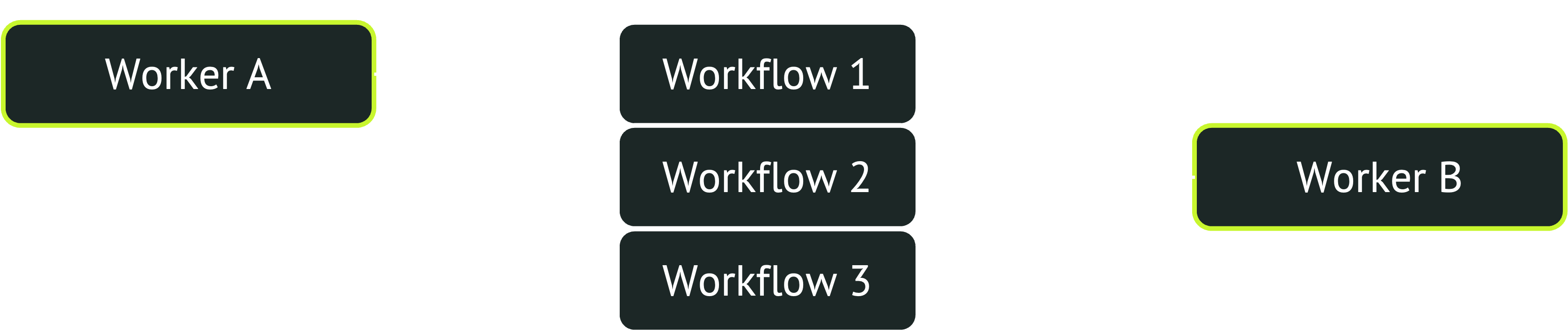

The problem is that if you have many workers concurrently pulling new tasks from the queue, they all try to dequeue the same workflows. However, each workflow can only be dequeued by a single worker, so most workers will fail to find new work and have to try again. If there are enough workers, this contention creates a bottleneck in the system, limiting how rapidly tasks can be dequeued.

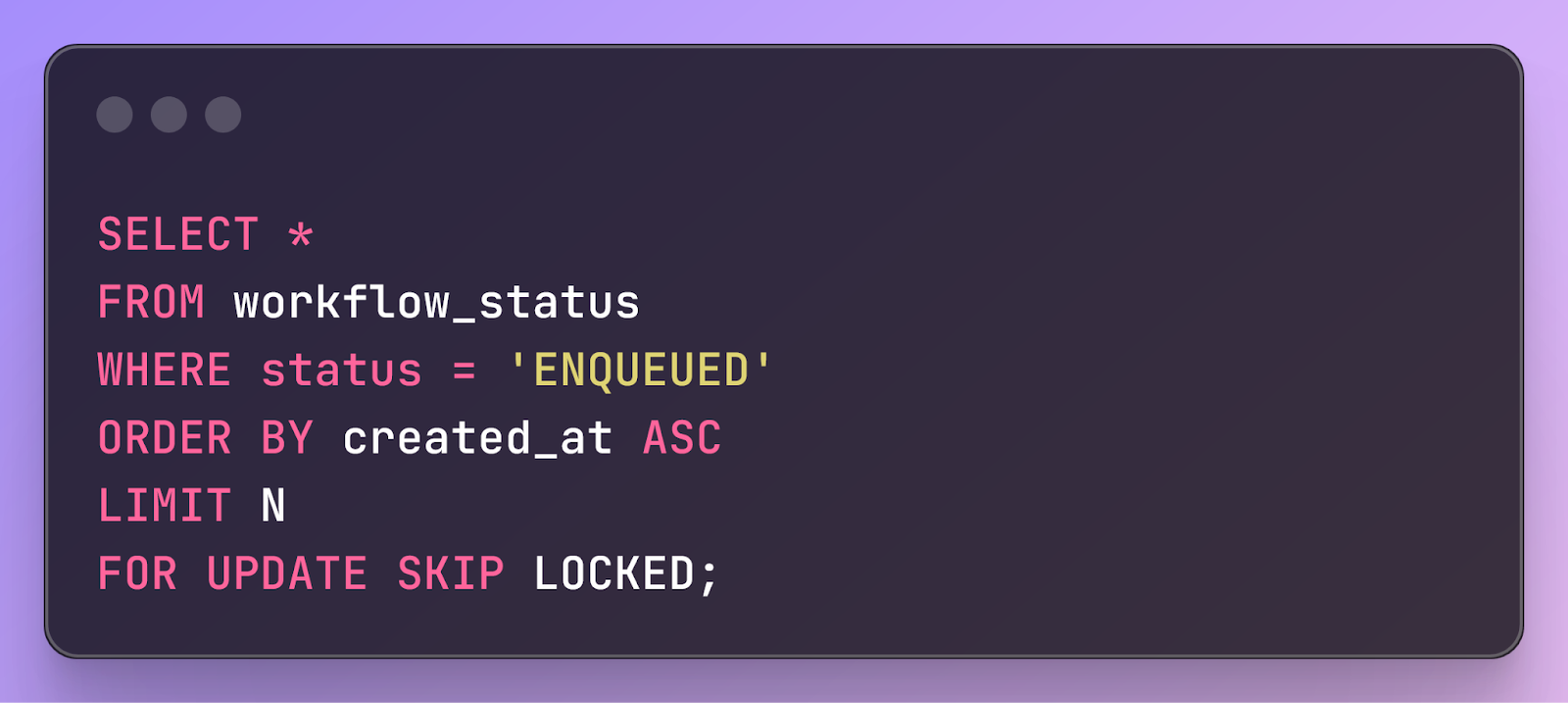

Fortunately, Postgres provides a solution: locking clauses. Here's an example of a query using them:

Selecting rows in this way does two things. First, it locks the rows so that other workers cannot also select them. Second, it skips rows that are already locked, selecting not the N oldest enqueued workflows, but the N oldest enqueued workflows that are not already locked by another worker. That way, many workers can concurrently pull new workflows without contention. One worker selects the oldest N workflows and locks them, the second worker selects the next oldest N workflows and locks those, and so on.

Thus, by greatly reducing contention, Postgres enables a durable workflow system to process tens of thousands of workflows per second across thousands of workers.

Making Workflows Observable

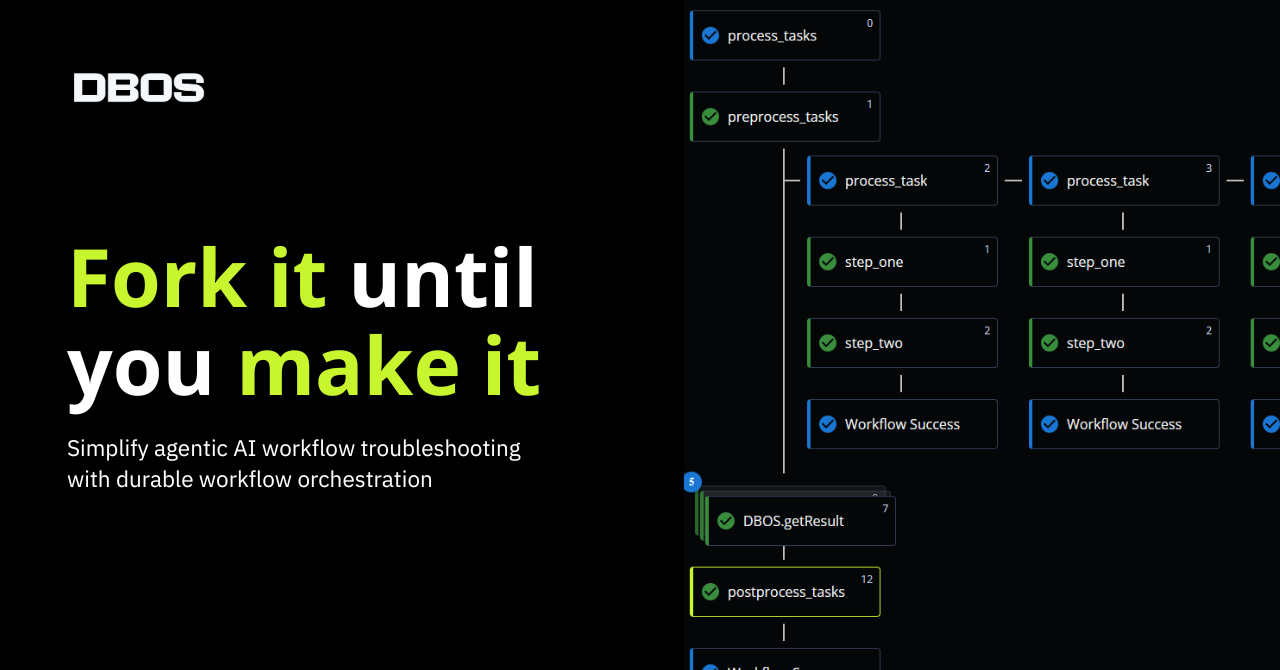

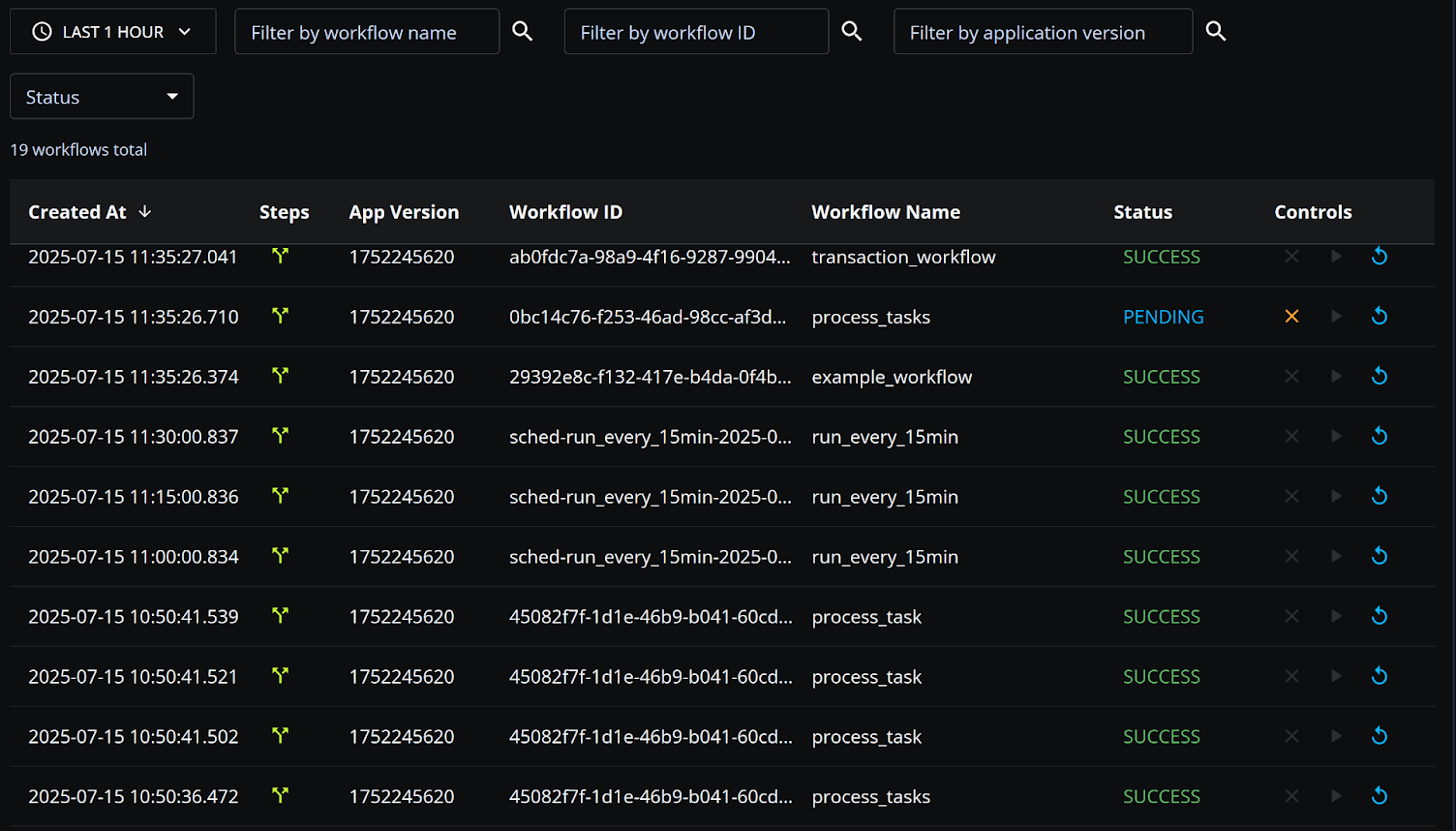

One benefit of durable workflows is that they provide built-in observability. If every step in every workflow is checkpointed to a durable store, you can scan those checkpoints to monitor workflows in real time and to visualize workflow execution. For example, a workflow dashboard can show you every workflow that ran in the last hour, or every workflow that errored in the past month:

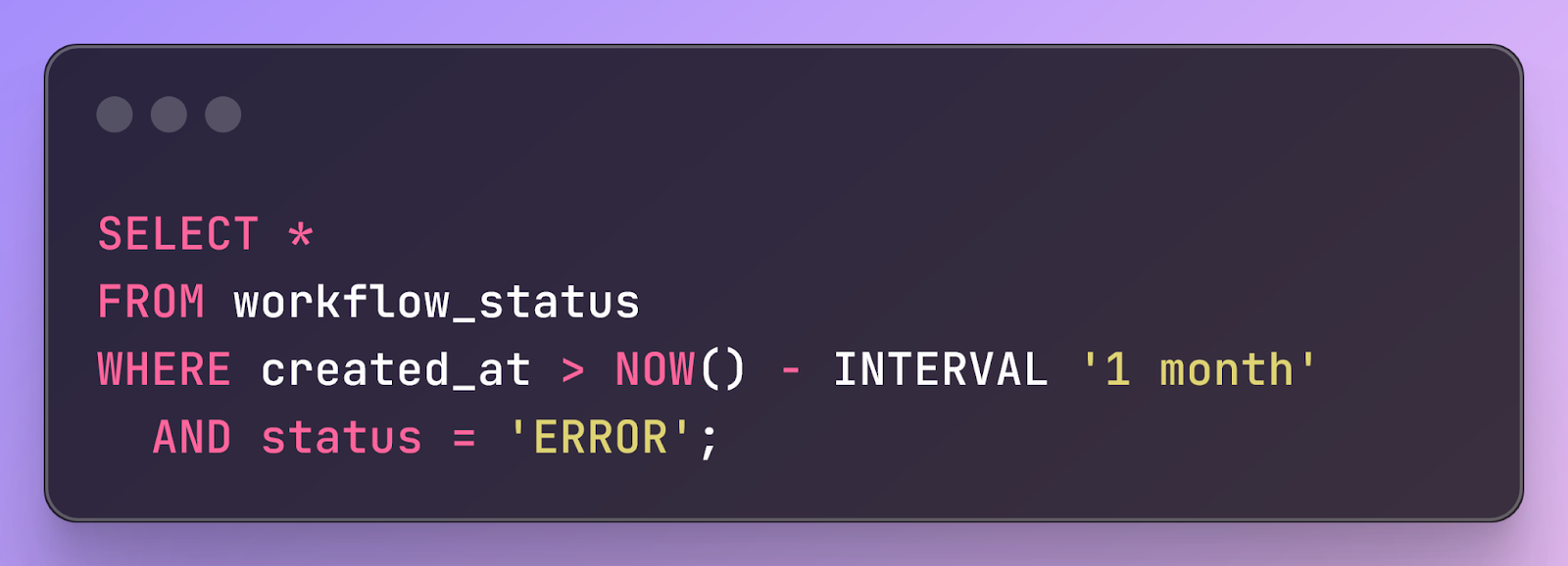

To implement observability, you need to be able to run performant queries over workflow metadata. Postgres excels for this because virtually any workflow observability query can be easily expressed in SQL. For example, here’s a query to find all workflows that errored in the last month.

These queries might seem obvious, but it's impossible to overstate how powerful this is. It's only possible because Postgres's relational model allows you to express complex filtering and analytical operations declaratively in SQL, leveraging decades of query optimization research. Many popular systems with simpler data models, such as key-value stores, have no such support.

Postgres also provides the tools to make these observability queries performant at scale (>10M workflows): secondary indexes. Secondary indexes allow Postgres to rapidly find all workflows that have a particular attribute or range of attributes. They’re expensive to construct and maintain, so they have to be used carefully: you can’t index every workflow attribute without adding prohibitive overhead.

To strike a balance between query performance and runtime overhead, we added secondary indexes to a small number of fields that are the most selective in frequently run queries. Because most workflow observability queries are time-based (typically a dashboard displaying all workflows in a time range), the most important index is on the created_at column. We additionally added indexes to two other attributes that are frequently searched without specifying a time range: executor_id (users often want to find all workflows that ran on a given server) and status (users frequently want to find all workflows that ever errored).

Implementing Exactly-Once Semantics

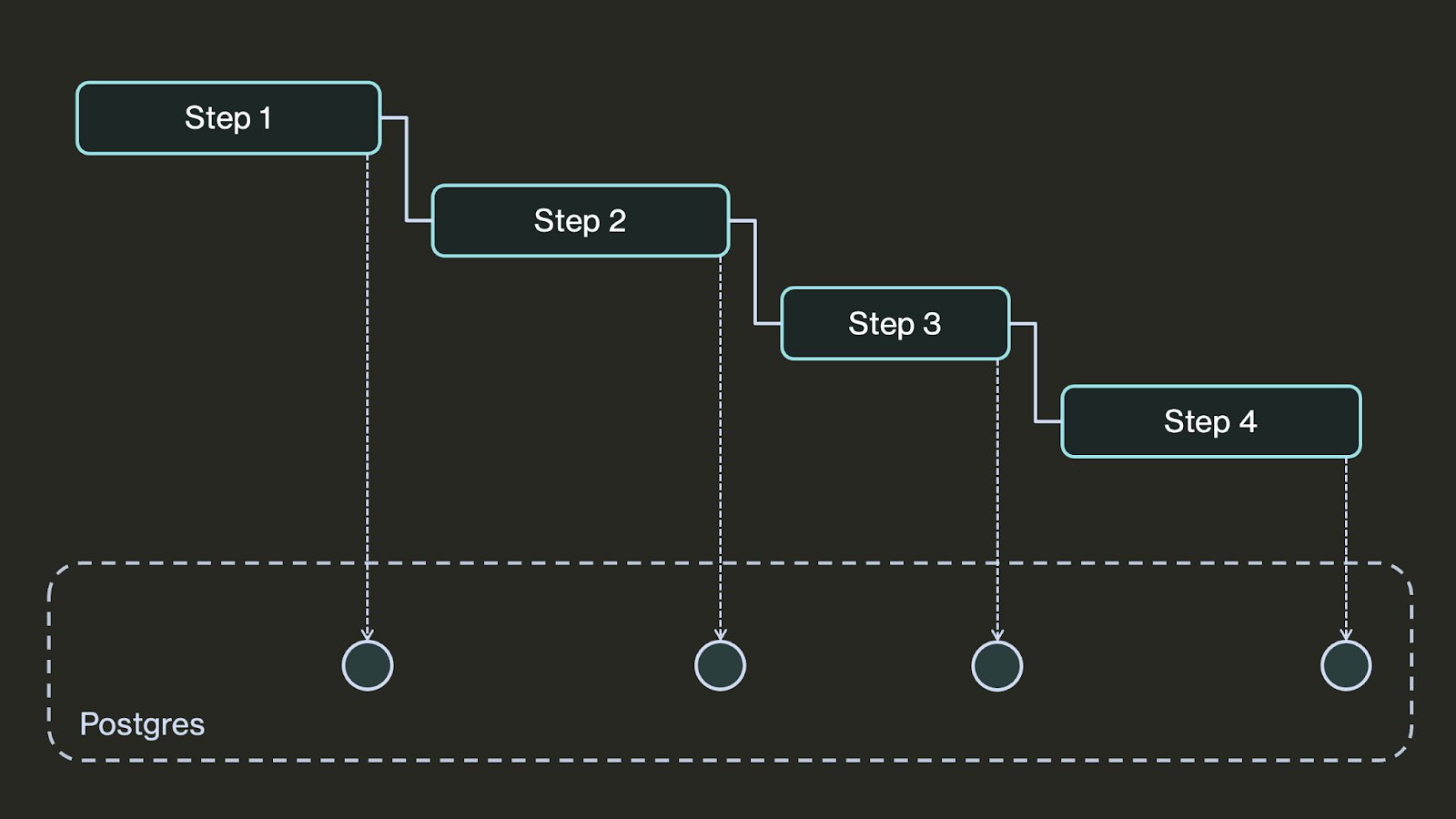

Typically, durable workflows guarantee that steps execute at least once. The way it works is that after each step completes, its outcome is checkpointed in a data store:

If the program fails, upon restart the workflow looks up its latest checkpoint and resumes from its last completed step. This means that if a workflow fails while executing a step, the step may execute twice–once before the failure, then again after the workflow recovers from the failure. Because steps may be executed multiple times, they should be idempotent or otherwise resilient to re-execution.

By building durable workflows on Postgres, we can do better and guarantee that steps execute exactly once–if those steps perform database operations. To do this, we leverage Postgres transactions. The trick is to execute the entire step in a single database transaction, and to “piggyback” the step checkpoint as part of the transaction. That way, if the workflow fails while the step is executing, the entire transaction is rolled back and nothing happens. But if the workflow fails after the transaction commits, the step checkpoint is already written so the step is not re-executed.

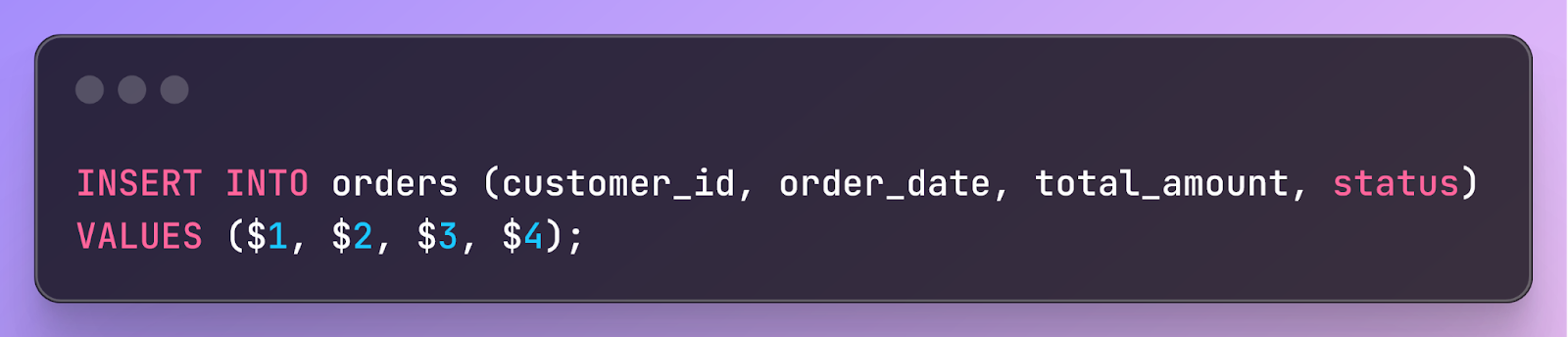

For example, let’s say a step inserts a record into a database table

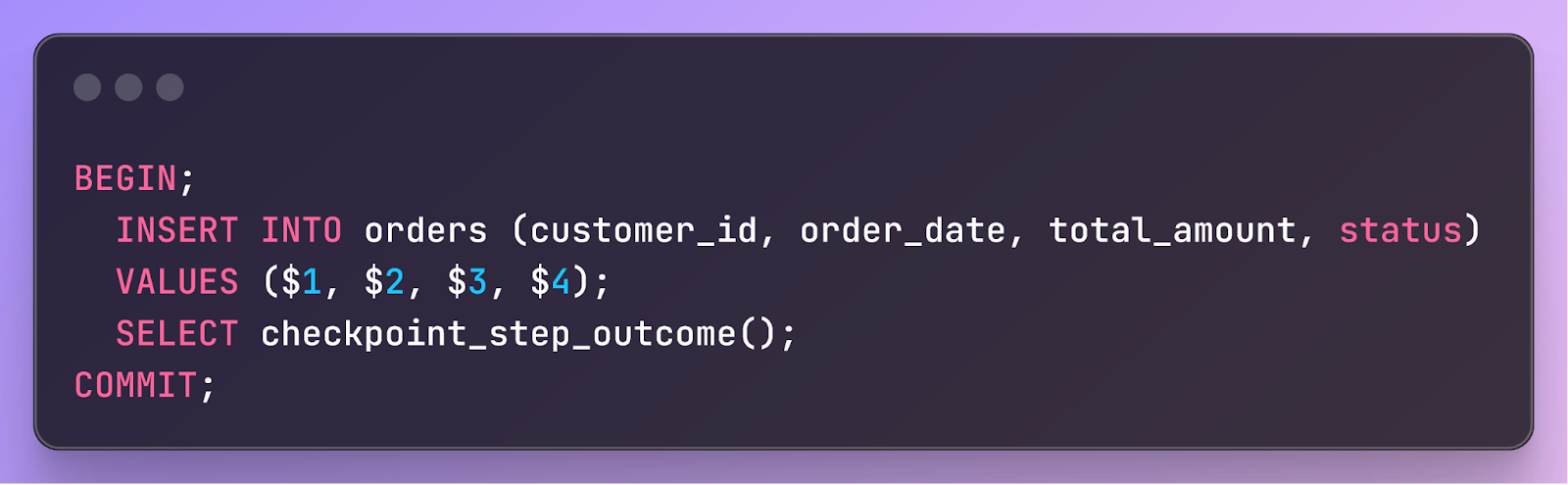

This step isn’t idempotent, so executing it twice would be bad–the order would be inserted into the table twice. However, because the step consists solely of a database operation, we can perform the step and checkpoint its outcome in the same transaction, like this:

Thus, the step either fully completes or commits (including its checkpoint) or fails and completely rolls back–the step is guaranteed to execute exactly once.

Learn More

If you like hacking with Postgres, we’d love to hear from you. At DBOS, our goal is to make durable workflows as lightweight and easy to work with as possible. Check it out:

- Quickstart: https://docs.dbos.dev/quickstart

- GitHub: https://github.com/dbos-inc